TL;DR

Store events in your database, and construct the current state of your database from those events. Keep side-effects separate (like emails being sent to users). Endpoints become open-ended and asynchronous, and you can track the state of your database throughout time (almost like Git).

Intro

My team and I are several months into a move from a traditional RESTful implementation (which is referred to as “active record” and is arguably the most widespread concept taught in web development) of our server to a more event-driven approach. If you haven’t read much about event-driven architecture (EDA) or event sourcing, I would recommend taking a look at this easy-to-follow slide deck (it should take about 10 minutes or so to get a basic idea of what’s going on). If you prefer not to read that…

Here’s a quick rundown of some of the basic concepts

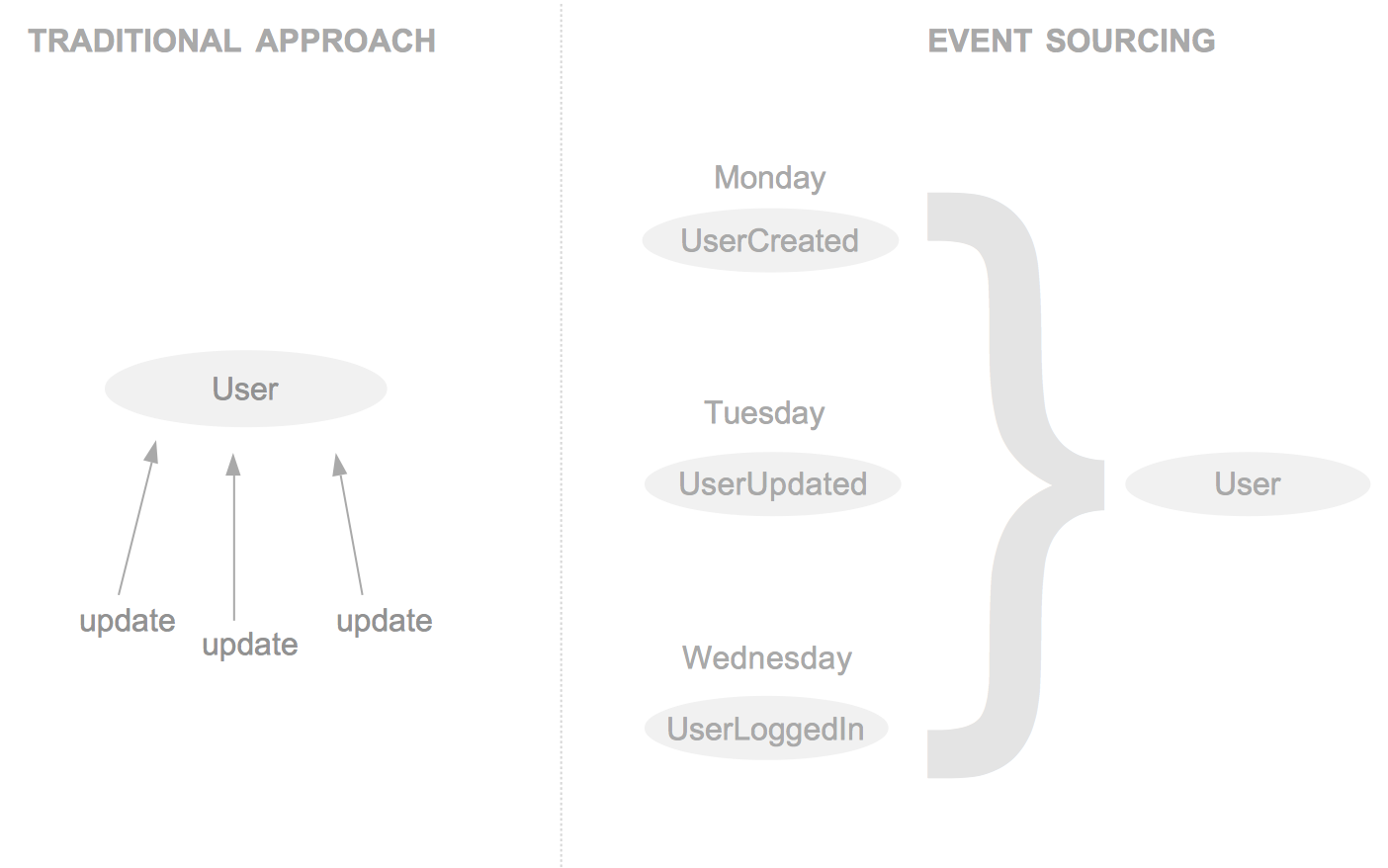

- “Entities” (records in your database) are modeled as events (for example,

UserCreatedwould be an entity). - Your stateful objects (something that would traditionally be a

Userobject or whatever) are derived from your events. - In theory, if you only kept a backup of your event entities, you should be able to reconstruct the most up-to-date state of your entire database.

Instead of mutating an object over and over and losing any notion of what led the object to that point, you can instead keep a timeline of the object and derive its current state. It’s like having a history of every object in your database. Kind of reminds me of Git.

For performance reasons, every time some requests, say, user/1234, you don’t want to recompute that user object based on the events that led up to that point (UserCreated, UserUpdatedEmailAddress, UserLoggedIn, etc.), but instead, every time an update/delete occurs, you can just store the current state of whatever that object is in a separate table and query for that on any GET request.

In other words, new events trigger updates, and GET requests query for the stateful object itself. This is almost like a cache.

In other words, this is a very close model of real life. Things happen over time, and the current state of anything is just the sum of the things that happened to it.

What can the endpoints look like?

Something like /api/1.0/userCreated.

One approach is to model your endpoints as events themselves. In other words, the endpoints have a semantic meaning for their corresponding entity, just like any other traditional RESTful endpoint. However, this approach lends itself to being a bit more open-ended and a bit less procedural. Additionally, all endpoints become basically either a GET or a POST (similar to “REST without PUT”), and side-effects are processed asynchronously on the backend.

That last point about side-effects is important, because if you were to reconstruct your database from your events, you would want to do so without, say, triggering emails being sent to users, etc. The side-effects should be encapsulated in a set of logic seperate from the event creation itself (and endpoints are a great mechanism for this).

Some benefits I’ve encountered

Loosely coupled, open-ended endpoints

This has been absolutely fantastic. For most operations, our client application just sends a GET for a current stateful object, or a POST to create an event. That’s it. If you’ve ever deployed an iOS application to the App Store, you’ll know it takes about a week (sometimes shorter, sometimes longer) to get approved. This means that if you have a bug in your client application, the fix takes the sum of the time it takes you to:

- Receive a complaint from a customer

- Find out why the bug is happening (“well, it was working on my machine?!”)

- Fix the bug

- Code review

- Do some QA

- And then, get App Store approval

This means you need to remove flow of control from your client application as much as possible, and move that control to your server. This is pretty trivial in most cases with open ended endpoints that simply respond to events.

We have continuous integration set up through CircleCI, which means that once we merge in Github from develop to staging, or staging to master, our server automatically deploys. This means that if we can keep as much logic as possible on our server, we can just deploy our server as often as we want to fix bugs that we encounter (this is obviously useless, however, if it’s a client UI bug).

Backend becomes asynchronous

This is huge. This means that essentially all side effects happen inside workers. So the only response that gets sent back to the client is either something like a 401: Unauthorized, 500: Internal error, or 200: Success. These responses are only those of the event creation itself. Things that might take a shit ton of time (like making a third-party service send an email to user who just signed up) can take place in the background.

An asynchronous backend can be implemented without an event-driven architecture (for example, by making traditional, RESTful, active record endpoints kick off async workers), but these approaches mesh very well together.

Some drawbacks I’ve encountered

Lots of entities

Events are entities, and, well… entities are entities too. In other words, if you store both events and the current state of your database, then you have a big database.

Backend becomes asynchronous

You’ll notice the second point was mentioned as both a benefit and a drawback. If your endpoints operate asynchronously, this means that you can only rely on sending an HTTP response for the creation of the event itself. That’s it. No client logic can depend on any subsequent operations or side-effects that take place on the server, unless you implement some sort of two-way communication via polling, web sockets, etc..

For example, say we want to prevent users from posting an ad for their used motorcycle on our app unless they’ve verified they’re email address. In a traditional, synchronous, active-record approach, we might do this:

POST /advertisement BODY: { type: 'motorcycle', make: 'Harley Davidson' }- Server checks

user.emailVerified === true? - If not, respond with, say,

401: Unauthorized - This response triggers logic on the client to show a prompt asking for the user to enter their email address in order to be sent an email with a link to verify it

This works great, if the backend is synchronous. What’s left to be discovered is the best approach for processing complex logic such as this with an asynchronous backend, which requires a different frame of thinking (something we’re still working on figuring out).

Some final thoughts/questions

Deletions

Do you want “soft deletes” or “hard deletes”? In other words, do you want to actually remove a stateful record from your database, or simply mark it (via a flag) as “removed” or “deleted”, or whatever?

Diffs

Since this approach is already closely related to Git, one of the only major things missing is the ability to “diff” objects. These diffs could be stored inside the event itself:

// UserUpdated event

UserUpdated = {

user_id: 'auth0|123456',

email: 'new_email@gmail.com',

updated: [

{type: 'MailingList', _id: 'aXd45', email: 'new_email@gmail.com'},

{type: 'User', _id: 'bgg7x', email: 'new_email@gmail.com'}

]

}There are still many questions to be answered, and lots of cool things that can be implemented here. It is a shift in the commonly-taught paradigm (the “active record” approach). I am excited to learn more from others who have experience with this! Thanks for reading, and feel free to chime in in the comments below.